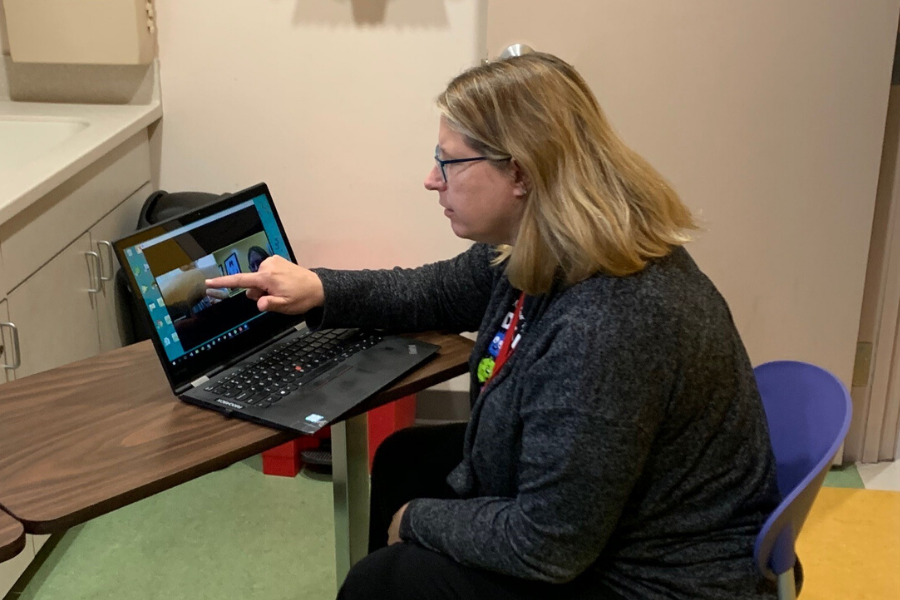

During a recent video call with a patient, a medical provider from the Henry J. Austin Health Center (HJAHC) in Trenton, New Jersey, peeked at the area they could make out behind the patient on the small video screen. They could see they were living in close quarters, sharing a small apartment with three other people.

“My uncle has COVID-19,” said the patient. “We live together. How can I socially distance myself from them?” Immediately, this short interaction gave the provider a rare intimate look into the patient’s life, all through a video screen.

“Providers have said they are getting a snapshot into the lives of their patients like they never had before,” says Pediatrician Dr. Kemi Alli, CEO of HJAHC, which is supported by Children’s Health Fund. “It helps our providers understand the complexities of the lives of those we are serving…There are some remarkable benefits to this new world.”

This “new world” is telehealthcare, a method of remote healthcare delivery that has existed for years but had never truly become mainstream, until now. Almost overnight, and with support from major funders like PepsiCo, providers across the country have adopted it, using platforms like Doxy.me, Zoom, and even FaceTime and phone calls to help safely provide care while social distancing. Children’s Health Fund was an early supporter of telehealth, first through our partnership in South Florida and then with several of our other national partners. Later, the organization began working with the Center for Rural Health Innovation (CRHI), national leaders in telehealth, which deployed a school-based telehealth program to serve children in rural North Carolina in 2011.

For a long time, telehealth technology and modules for health records have existed, but just needed to be turned on, says Amanda Martin, executive director of CRHI. “The telehealth world was well-poised to respond to this situation,” she says.

The programs supported by Children’s Health Fund across the country have accelerated and enhanced their use of telehealthcare to continue serving children and families in marginalized communities who, because of historical oppression and systemic inequities, are most vulnerable to the impacts of the pandemic. Now, these programs are operating almost entirely remotely while continuing limited in-person care for patients who urgently need it.

Dr. Sarah Beaumont and her team with the program we support at Phoenix Children’s Hospital started providing telehealthcare to the patients they serve including those who live at shelters and group homes. Before this, the program wasn’t using telehealthcare at all. Dr. Beaumont says it has made access to care, particularly subspecialty care, easier for some patients because it eliminates transportation barriers. This has been helped by computer rooms set up by some shelters for patients who don’t have smartphones or access to wireless.

She has even observed that young people seem even more comfortable with a remote visit than an in-person one.

“As a provider, not being able to see someone in person is challenging. But a lot of youth are into phones and electronics. You’ll get more disclosures and they are more comfortable sharing personal information that is important in diagnosis and treatment that they may not have shared during a first visit, but because they are in their shelter home and they may be more comfortable there, they are more willing to share,” she explains.

Dr. Alli in Trenton has observed a similar element with her team. “I have to say, through telehealth, the connection between provider and patient is still able to be made. I’ve been remarkably surprised by that.”

On her team, efficiency has increased exponentially because providers are able to see more patients in less time because physical logistics are no longer a factor.

Lisa Ortega, a patient at the CHF-supported Bronx Health Collective, says telehealth was essential to help her stay connected to her therapist to help her cope with the anxieties brought on by this crisis. “At the beginning, I had a phone consultation with my therapist but it didn’t work. I needed to look her in her eyes. I need that kind of communication,” she said. “But when we finally got on Zoom, I could feel my shoulders going down, my body relaxing.”

This new era has forced many teams to be creative in recognizing how they can reach patients, provide quality care, and also protect patients’ privacy and safety. Serving people without homes, for instance, who have very little privacy in everyday life, Dr. Alli’s team will ask if there is a private space at a community center or private public bathroom they can go to during the appointment. And they have realized they can provide more care remotely than they originally thought, particularly for pediatric well-child exams. They have talked about sending families measuring tape and scales so they can be involved in measuring a child’s growth, for instance.

At her program and in many communities across the country, leaving the house can be extremely challenging for mothers with several children and older adults relying on public transportation. For these patients, reaching a provider remotely without having to leave the house is incredibly helpful.

This ease of access is also helpful in the tele-mental health space, says Jannet Rivera, mental health counselor with Counseling In Schools (CIS), which partners with our Healthy and Ready to Learn initiative to provide mental healthcare to children at public schools in the Bronx and Harlem, New York.

This is a particularly difficult time for both children and parents, especially those who were already impacted by poverty-related stressors and trauma. But crucial pieces of mental healthcare assessments can be lost in remote interactions. “It can be very challenging helping end panic attacks and eliminate anxiety when children are home. I miss giving and receiving hugs from students and parents. Hugs help reduce some fear, anxiety and stress,” Jannet explains.

Privacy and comfort, central aspects of healthcare, are also major concerns with remote visits. “Some parents and caregivers, despite the request for privacy and confidentiality, may be hearing the conversation between myself and the student,” Janet says. “So the student may feel uncomfortable and a lot can be missed.”

Poor internet connections and choppy reception can also make remote appointments very difficult. “I’d say 96% of our patients have a smartphone and others have old flip phones. The vast majority have technology they can use. But that small percent that don’t…I worry about them,” says Dr. Alli in Trenton.

These technology restrictions extend beyond access to individual devices and reflect a deeper digital divide. In some parts of the country, such as rural areas, high-speed internet is simply not available. Lower-income communities and communities of color in particular are often unable to afford broadband internet, pointing to systemic poverty and racism.

Being propelled into telehealth has allowed providers to consider how it will continue to be part of their programming going forward, and many are excited by its possibilities and the solutions it offers patients. Amanda Martin in North Carolina just cautions providers to be mindful of quality going forward. “What my organization does is a complete exam with two-way audio/visual, with peripheral devices to allow for a full exam…I understand in this urgent time there is a need for just video or just phone, but in the long run we need to realize the care we can provide with the modalities available to us.”

Dr. Alli does recognize one area of care that can’t be replicated remotely: the value of what is called the laying on of hands, or physical touch as part of a medical exam. “For some of our patients, the first time they have had a positive experience of someone touching them, is when they come to us. That has never been lost to me.”